Simon Blumenfeld Jew Boy

A somewhat confrontational title which, according to

Ken Worpole in his comprehensive introduction here, still ruffles sensitive

feathers. But the book itself is a somewhat less gritty read than the other

between-the-wars novels published by

London Books Classics

by the likes of Robert Westerby and Gerald

Kersh, reviewed below. Alec works in the rag trade and is looking to get

laid and/or married very soon. His anguish at achieving neither of these goals

is expressed against a background of 30s political protest and the details

of Jewish life and observance. You'll maybe be reminded more of Rosamund

Lehmann and Elizabeth Taylor in the emotional and playful tone, rather than

the lowlife criminal atmosphere we expect from LBC. Alec and his mates and

their demands and girlfriends make for more of a slice-of-life narrative

than the knife-fights and thieving we have come to expect from working-class

types in the mid-20th century. The politics and plotting can seem a little

dated and naive(ly hopeful), but this is still engaging and readable, with

much evocative period detailing and attitudes.

Jessie Burton Hidden Treasure

The day that this book begins is a busy one for Bo, a

Battersea mudlark. Her brother goes off to war, the Thames, always a

presence for her, speaks to her, and she finds a bejewelled and magical

disc representing the moon. The last two events seem connected, and then

along comes a boy from the other side of the river who the river has also

communicated with, and who knows more about the strange disc. The

characters who turn up, as things become a little clearer, are rarely what

they seem, or claim to be, but the deception and peril are mild, this

being a book for 4-9 year olds. The story is nonetheless involving and

magical, and reeks of the river.

Norman Collins

London Belongs to Me

First published in 1945, this has a fair claim to

being one of the

novels of London life during WW2. It takes the inhabitants of the flats

on all floors of a big old house in Kennington from 1938 on into the

war. It's a slice of real humanity at the time, taking in low life,

family life, faded glamour, life ending, lives beginning and all the

actions and emotions, noble and despicable, that get stirred up along

the way. Words like teeming, tapestry, Dickensian, and flipping long

are all justified. Along the way there's incidental pleasures, like the

appreciation of the kind of crap that was eaten before the Italian and

Indian food fads of later decades. You could say that it's soapy, but

that would be unfair - this is what soaps want to be when they grow up.

It's also very funny, in a way that keeps you grinning all through, if

not laughing out loud. It's not cool (or cold) enough to be a cult

novel, and not idiosyncratic or deep enough to be a real classic. But

it is nonetheless a soundly enjoyable and moving read. An odd thing I

noticed is that, although there is next to no travel on the Underground

in this novel, the majority of its locations, and even places just

mentioned in passing, are on the Northern Line.

|

|

Maureen Duffy

Wounds 1969

The first of the novels in Duffy's London trilogy takes us into the minds of

various disparate characters whose connections become apparent as the pages

progress. This streaming style makes for some occasional confusion, as a

section starts and you take time to realise who it deals with, but not

so much as to spoil the flow. Early on there's an odd recurrence of horse

memories, or metaphors, and a common-ground pub emerges. A lesbian gardener of

mature years starts us off, and we pass through various colours of skin and

ages and classes, with wartime memories still strong and damaged lives a

common thread. We return regularly to a pair of undamaged lovers in bed,

talking loving tosh and exchanging fluids, in a way that seems to be ironic

counterpoint to grim real life, but I suspect is not so simply intended. The

London (and period) flavour is strong, but more in spirit than topographical

description - mention of a common and some pub names is about as specific as

the scene-setting gets. The fun-fair later on may well be Battersea, so the

common might be Clapham. One of the characters, a mayor, is pondering the

impending amalgamation of some London boroughs, which happened in 1965 -

some precise dating then. A novel very much of its time, in style and

content, but full of flavour and worth the effort.

Capital

1975

This second book in the London trilogy can now be seen as an

early incarnation of the whole Ackroyd/Sinclair thing about London's

history going in many more directions than

simply forward and back in a straight, historically-accurate, line.

Down is the

direction dealt with here, with the central character, Meepers,

obsessed with

the bones beneath our feet and the stories they tell. And the stories

they tell,

mixing history and myth, are interspersed with his story in a

time-jumbling way

which was once seen as scarily modern, as Paul Bailey observes in his

introduction, but which we are now more used to. Meepers's major

obsession is

whether the post-Roman period of London's history is really as dark as

it's

painted. (The Museum of London represents this time as simply a

pile of fragments

of classical architecture strewn amongst weeds.) This isn't as gothic

as an Ackroyd, or as dense as a Sinclair, but it's pleasingly dark in

places, with the

past painted in all it's grubby grimness, but with a balancing element

of

humanity and warmth you'd expect from a book written by a woman, if

you'll

pardon my stereotyping. It's nicely of its time - a time when some

proper bus

routes ran open-top buses, not just tourist trips, and when you could

share a

flat in London for £7 a week. One of the key London novels.

Londoners 1983

The last one. |

|

Christopher Fowler

Full Dark House (Bryant & May Book 1)

Beginning a series with the death of one of your named

protagonists seems a little unorthodox. Events in the present day relate back

to our heroes' first case back in a blitz-ravaged West End. A series of

murders at the Palace Theatre are united in their gruesomeness and inexplicableness.

The Peculiar Crimes Unit is called in and prove that it's not just the

crimes that are peculiar. As it's Bryant and May's first case together the

mutual sizing-up gives us sharp glimpses of their characters and hang ups, and looking

back allows hindsight and a broader perspective on their peculiarities.

Bryant and May are a bit Holmes and Watson but with Bryant a bit more

peculiar and the relationship a bit more equal. All very clever, and the

detail and atmosphere that the author provides and evokes conjures a London

that gets up your nose and clings to your clothing. The realities of life

during the blitz have never been more...real. The murders turn out to be all

dictated by the stories contained in Greek myths, or do they? All very

clever, as I say, and I look forward, but with a little trepidation, to

reading the rest.

Anthony Frewin

London Blues

The

author's day job was assistant

to Stanley Kubrick, but here he explores less reputable, but more

frequent, film-making. It's the 1960s and our hero works in a Soho café

and

becomes involved in pornography, progressing from taking grainy snaps

to

shooting grainy 25-minute films with titles like Schoolgirl Frolics

and

The

Randy French Maid. His shady dealings with Stephen Ward get him

embroiled in the Profum o affair. The book paints an authentic-seeming picture

of London in the mid-60's, a time when the minor railways could still be

said to 'criss-cross London with a secret logic of their own'. The locations

and odd facts keep the London-interest factor high. (Evidently if you wanted

pornography in London in the 18th or 19th century

you went to Holywell Street which was amongst a warren of streets - demolished

in 1901 - at the bottom of Kingsway, where you'll now find the Aldwych

and Bush House. A character in

Fingersmith above ventures

here.) The relationships are believable and you care about the

characters - both further signs of a book well worth reading. o affair. The book paints an authentic-seeming picture

of London in the mid-60's, a time when the minor railways could still be

said to 'criss-cross London with a secret logic of their own'. The locations

and odd facts keep the London-interest factor high. (Evidently if you wanted

pornography in London in the 18th or 19th century

you went to Holywell Street which was amongst a warren of streets - demolished

in 1901 - at the bottom of Kingsway, where you'll now find the Aldwych

and Bush House. A character in

Fingersmith above ventures

here.) The relationships are believable and you care about the

characters - both further signs of a book well worth reading.

Neil Gaiman Neverwhere

When an injured

girl called Door falls into a

London street, from a door that isn't there, at the feet of Richard

Mayhew, he

stops to help her without thinking. And so begins his descent into a

subterranean

London where each dark tunnel leads to strange places, stranger people

and odd

creatures, and the danger of death. Myths from London's past are played

with and place names come alive,

as London's history takes on new dark depths. It's all big gruesome

fun, with a

couple of the nastiest vampire hit-persons you're ever likely to meet.

The

writing owes a lot to Terry Pratchett, in its humour and its timing

and Gaiman did collaborate on a novel with Pratchett, so a little

rubbing off is

understandable. He'd obviously been reading a bit of Anne Rice too.

This one is

played a lot for laughs, albeit gruesome ones mostly, and does not have

the

conviction and depth of characterisation of the later and better

American

Gods, but it's still essential reading for fans of London's myths and

tunnels. One small gripe - why does the author, an Englishman writing about London,

refer to sidewalks? Pavements is what we have over here, not sodding

sidewalks.

Neverwhere was made into a TV series in the UK in 1996 , which came out on

DVD in the UK in 2007, the same year that a graphic novel appeared. In

2016 an edition of the book illustrated by Chris Riddell appeared. It's cute, with many

full page drawings and loads of little ones in the margins too. In 2019 the

TV series came out on Blu-ray, upscaled. |

Jeremy Gavron An Acre of Barren Ground

This one's a sequence of

self-contained, but sometimes strangely linked, chapters dealing with the

history of Brick Lane. It covers a span of Centuries, but I've put it here

in the early-20th as then was the area's most famous time, possibly. There's

also a wide range of formats, including quotes from news reports, a poem,

photography, a graphic novel, and other forms of fruitfully fractured prose.

Major themes unsurprisingly include the lives of Whitechapel's various waves

of immigrants, anarchist politics, and the Ripper murders, but these are far

from all, as characters briefly come to life and are left behind as you're

propelled into another different century before you can catch your breath,

inviting the use of words like 'kaleidoscopic' and 'rich tapestry'. A topic

new to me was the corruption of the area's brewing industry. Calling this

fractured, if fascinating, read a novel is pushing it a bit, but it covers

the ground, as it were, and points to further investigation of its sources,

listed at the back. One section deals with the bird trade back when the

Sunday market was called Club Row, after the street where small animals were

sold, sometimes out of street-corner dealers' pockets, until the law caught

up with the painted birds and poor conditions. It brought back strong

memories for me of peering into cages at balls of fluff and feathers on Sunday mornings

in the 60s with my Dad.

Graham Greene

The Ministry of Fear

My primary prompt to read this book was a love of

Fritz Lang's film of it. Large liberties with the source novel were

reported, and such turns out to be the case. The memorable opening of the

film, for example, involving a man's release from incarceration, his

attendance of a garden fete (at night!), and the strange business of the

blind man on the train to London and the pursuit through the weird

countryside, are all Lang's invention. In the novel our hero's story is

picked up in London, where he happens upon a fete in a city square, and the

winning of the fateful cake and all the business with the fortune teller

happens here. But the main difference is how the later explosion which

propels him into the hands of the police in the film, in the book puts him

happily into a nursing home, with no memory of how he got there. And the

whole business of how his not remembering the almighty guilt-inducing

tragedy of his life leads to his becoming a different, and happier, man,

forms the major, and most memorable, theme of the book. So the novel

provides a different satisfaction from the film's, but with eerie echoes. It

also paints a vivid and authentic picture of life during the blitz, where

you can turn a corner into a familiar street, once full of memories, and it's

all gone. At one point Greene talks of a 'strange torn landscape where

London shops were reduced to a stone ground plan like those of Pompeii'.

Patrick Hamilton

Twenty Thousand Streets Under the Sky

Set in London between the wars, this is a trio of stories

dealing with the lives of a trio of characters connected with a pub. The pub

is called The Midnight Bell and is situated on Warren Street, near the

junction of Euston Road and Tottenham Court Road. (There's a real pub in the

area called

The Prince of Wales Feathers which was a favourite of

Hamilton's.) The characters are Bob, the waiter, and Ella, the barmaid of

the pub, and the prostitute for whom the waiter fatally falls, called Jenny.

The first book painfully details Bob's desperate and self-deceiving need to

imagine her love as he spends all his money on her and misinterprets her

need and deception. The second part concentrates on the episode in Jenny's

early life that formed her character and career. The last part is centred

around Ella. It's a very London-exploring novel - Soho especially gets

walked through comprehensively, and there are excursions into the fleshpots

of Hammersmith and Chiswick. And like most novels of the early 20th century

reading this makes one mourn again the passing of the Lyons Corner House. If

you'll pardon a flurry of clichés I have to say that the characters live and

breathe and that Hamilton does a definitely Dickensian thing with humorously

decorous language and lovable/hateable low-life characters. He lived the life, of

course, drinking to excess and an early death, and having his own unhappy

relationship with a prostitute just prior to this book's publication. An essential gem of London fiction.

Tobias Hill Underground

Women are getting pushed under Tube trains and a tube worker

becomes obsessed

with a rough-sleeping woman who looks a lot like the victims. Beyond

this bald

statement of plot is woven a story of secret tunnels, security, threat,

and much

real dirt. There's a parallel plot strand telling of our hero Casimir's

childhood in post-war Poland, which alternates with the main plot

through the book, but which is fascinating enough in itself not to make

one

yearn for the return of he 'real' story. A novel to perfectly

complement

the facts and myths about the London Underground as touched on in my

dark

Tunnels

and Underground Stories page.

Gerald Kersh The Angel and the Cuckoo

Another rediscovered gem from

London Books Classics,

and you'll note the lack of inverted commas back there, as this truly is a

novel that'll repay your attention. The action revolves around Steve Zobrany,

the Hungarian owner of The Angel and the Cuckoo cafe, who sees good

in everyone, even Gèza Cseh and Thomas Hardy. These last two generate most

of the tales that spin off the story of Zobrany. The first is a sharp

operator who ends up in Hollywood, the latter an artist almost totally

lacking in feck. These tales span the first few decades of the 20th century

with two wars looming darkly in the background. The foreground lives here

are mostly low and bohemian, taking in cons and criminality aplenty. The

overall tone is humourous, but bittersweet - this is a book about life and

love and human weakness, not chucklesome set-pieces. Sometimes Kersh gets a

bit carried away into florid language and somewhat pointless excess, but a few

paragraphs skipped soon gets you back on track. This early-20th century

London underbelly stuff is becoming a bit unrare, but when it's chucking up

good stuff like this let's not complain. Kersh is also the author of

Night and the City, which was made into a famous film, or two. |

|

John Lanchester Mr Phillips

In which a middle-aged accountant gets out of bed one warm

July morning and does his usual commuting thing from Clapham into town, but this

is not going to be a usual day for Mr Phillips. He's just been sacked, you see,

and so he's just pretending to commute, and ends up having one hell of a day.

His walk through London, from Battersea eastbound into Westminster, is

recognisable in its sights and details, and makes for a fragrant picture of

London life and Londoner's habits as the Millennium turns. He thinks about sex a

lot too, and has a Nicholson Baker-like interest in the minutiae of life. He visits

his son, a sex cinema, and the Tate Gallery, amongst other places, and gets

involved in a bank robbery and street theatre. A believable and

compulsive tale - it's just like being there and doing it.

China Miéville King Rat

When Saul returns to his Dad's tower-block flat he doesn't relish a

confrontation, so he goes straight to his room and sleep. He's awakened by

big noises as the police gain entry. They drag him away and he notices the

ragged hole in the window through which, it turns out, his father had been

forcibly ejected a little earlier. So begins Saul's unique tale, during

which he finds out his mother was a rat, literally. The story mixes myth and

muck, modern music and violence, grime and murder - the result is a weird

and occasionally nasty tale of a man whose life becomes a big confusing mess

as he becomes aware of his background, and the nature of the man who is

pursuing him and murdering his friends. It's heavily wrapped up in the drum

'n' bass music scene of the mid-90s, and hence has dated a little quaintly,

as d'n'b has failed to live up to its promise as THE millennial

multicultural music and is now a pretty minor influence, surviving in its

mutation into grime.

But the breakbeats do add a sharp flavour to the mix of traditional

storytelling and urban degeneration, with horror-film touches. Not a book

you'll forget or read anything else like real soon, I think. Also

anyone who can get all elegiac about Willesden deserves our attention.

Un Lun Dun

This is a book for older children/young adults which

attempts to mix a bit of Buffy and recent Dr Who into Alice in

Wonderland, with added mobile phones and snappy youf-talk.

The story sees two teenage girls dropping into an alternative London, where all

the rubbish goes, and which is plagued by a sentient evolution our old 1950s

smog, here called Smog. One of the girls, Zanna, is the chosen one, who, it is

said, will come and vanquish all foes. The other is called Deeba and befriends a

milk carton called Curdle. There's a crack team of martial-arts trained rubbish

bins called The Binja, and the boss of the very handy broken umbrellas is called

Brokkenbroll. I know that I'm not the target audience here, but I can't see a

teenager having any more patience than me with a book whose plot hardly zips

along and rarely surprises, and which has a certain flatness of characterisation

and detail. There's masses of weird stuff all around, but not much texture. File

under Large Disappointment.

David Mitchell Utopia Avenue

The title of the book is the name of a band. Both are full of typical

1960s middle-class hippies and attitudes. The band have good gigs and bad

gigs, good friends and blazing rows, famous friends - 'hi David', 'Hi

Marc' - and puzzled parents. London glowers all around and is full of

dolly birds, pop stars and fag smoke. As the book begins the big-draw

well-brought-up female member has just had her duo broken up by her

partner skipping off to Paris, so she's all weepy and heartbroken, but

this schmaltz is countered by the mercurial-genius guitarist having an

interesting mental illness, and so prone to hallucinatory interludes. Add

to this all the older people who tell our male heroes that their hair is

too long and that they look like nancy boys, and that national service would

have sorted them out, and you have a novel seemingly inspired by 60s

sitcoms. But this is a serious novel by a big-name author, so there's more

to it, but not much. I managed about 25% but was still not

caring. Unambitious.

Michael

Moorcock

Mother London

This is one of the essential London

novels of the past couple of decades. It came out in 1988, has long been

out of print, but was reprinted in 2000, in a tasteful yellow-painted

brick binding, to tie in with the publication of a sequel, called King of the

City. It's the kind of novel you don't see on the New Novels shelves

anymore - a work of real imagination, and featuring a city you'll

both recognise and be surprised by. It traces London life from the Blitz

to the slightly subtler disaster of Thatcherism, through the eyes and lives of a

bunch of characters who may be mad, or who may just be tuned into the thoughts

of all their fellow Londoners. It leaps around in time but builds

up a picture and an idea of London that you won't soon forget and which

will probably skew your perception lastingly and totally. No, really.

The Whispering Swarm:

Book One of The

Sanctuary of the White Friars

And having not had a proper new novel out in 10 years, in 2015 MM suddenly

presents us with this puzzling offering. I say puzzling because it mixes

autobiography with (fantastic) fiction and also because the prose is oddly

simplified, like maybe he originally set out to write a children's or YA

book. The story tells of teenage Michael Moorcock's life and early career in

a very real and detailed 1950s London, centred on his home in a fictional

area near the Holborn Viaduct called Brookgate. As he starts out on various

literary careers he meets a monk who brings him to an oddly

untouched-seeming patch of the Medieval/Georgian/Victorian city where he

becomes smitten with a gorgeous highwaywoman and meets sundry other

characters he'd only previously dreamed of. But with the advent of the 1960s

and sex the boy convinces himself that it had all been a dream. Much

dropping of names and trousers ensues.

|

|

Alan Moore

The Great When

The author is the wild-haired and magusy author of many famous comics,

including The Watchmen, V for Vendetta and The League of

Extraordinary Gentlemen. The star of this novel, the first of a series

of four, is Dennis Knuckleyard, who is 18 and living in Shoreditch in 1949,

above the bookshop of Coffin Ada, his belligerent and consta-coughing

employer and landlady. As if the idea of a bookshop in post-war Shoreditch

wasn't fantastical enough... when he is sent to Berwick Street to collect a

job-lot of Arthur Machan novels and finds the box contains another book, a

dangerous book , it gets him propelled into Long London. This is the other

London which exists parallel to our London and which contains all Londons -

real or imagined - a sort of Fictional City if you will. The writing is

fruity and purple, generally, and when the action moves to Long London it

becomes seriously hallucinogenic and self-indulgent and even more hard to

follow. You'll find your attention skipping, but the real-London-set

language can be more easily followed and repays your stamina. The characters

are far from clichés and the dialogue is smart. Prince Monolulu plays a

crucial part, he having been the only black man you saw in post-war London,

my Dad always said. TheLondon evoked here hadn't changed much by the time I

was walking some of these streets - Spitalfields and Shoreditch are central

- in the 1960s, and playing on bombsites. This book is heavily indebted to

the 1980s psychogeographic novels of Ackroyd and Sinclair and there's

nostalgia in that too. The last chapter, where Dennis looks back from 1999

is, well, weird in another way. What next? We'll see.

Iris

Murdoch

Under the Net

Having been an all-consuming Iris fan in my 20s and 30s I thought that it

was high time - decades on - for a revisit. And where better to start

than the beginning. Her first novel jumps straight into her characteristic

philosophical and political concerns, this time dealing with a self-obsessed

translator of other people's works. As the book is set in the early 1950s

Jake is not called a slacker, but he does very little, lives off his

friends, drinks to excess, and sleeps on Embankment benches with the best of

them. His sense of his own wisdom and powers of perception is in no way

dented by his getting almost everything wrong. There's more humour than I

remember, some spectacular set-pieces (no, really) and the reading is easy.

Post-war London is authentically evoked, with Hammersmith something of a

centre. But there's also a lot of the action around the actual central City

of London, which is somewhat rare, with some of the characters actually

living there. Especially worthy of mention is a pub crawl around St Paul's,

taking in bombed churches, the shells of warehouses, and a midnight

skinny-dip in the Thames around the barges. Fragrant.

Flight of the Enchanter

Novel number two is set around Kensington and into

Chelsea. More rich people live lives of small problems and big drama, this

time united by the controlling charisma of a shady press baron. Not so rich

in London detailing this time, although the press baron's London home - four

houses in two rows knocked together to make a mansion of puzzling

interconnecting rooms with no passages or corridors - is a fascinating

invention. Set in the 1950s - a strange past time when a pale and perky

teenage girl-about-town would still wear petticoats. Psychologically acute

as ever, and readable, with some bizarre and funny set pieces.

Geoff Nicholson Bleeding London

An A1 example of the kind of book

this site is about - a book about London, a book which deals with London

as it is, and London as we think it is, and how the two can differ and

become closer. A Tarantino-esque thug with wit is down from Sheffield;

he's lost, but he's got an A to Z and a big gun and he's tracking down

the yuppies who gang-raped his girlfriend. The boss of a London walks company

attempts to put some meaning into his existence by walking up every street

in the city he (still) loves. The pair are doomed to meet,

and both get screwed and screwed up by a half-Japanese girl who thinks

maybe she IS London: "There are security alerts. There's congestion,

bottlenecks. Some of me is common...I have flats and high-rises." There's

maps, there's facts, there's kinky sex, there's a slight lull in the

middle as the conceits wear off and the plot coasts, but there's wit,

humour, informed love of London, Sharpe writing, and an imaginary bookshop

that truly deserves to exist. |

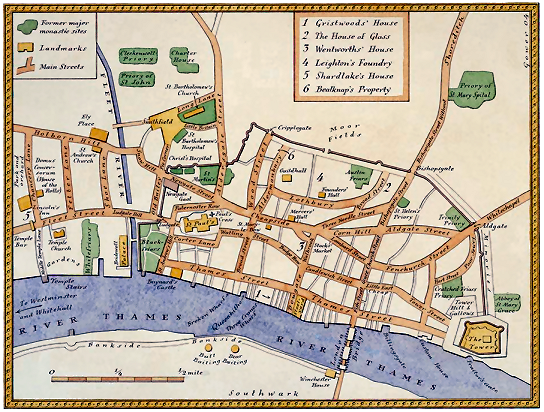

The

first book Dissolution takes

place against the backdrop of the dissolution of the monasteries and sees

Matthew Shardlake, lawyer, hunch-back and supporter of Reform, sent by

Thomas Cromwell to a Sussex monastery to investigate a grisly murder and the

theft of relics. There is solid history, gripping plotting and detail, and

atmosphere you can taste, but not a lot of London.

The

first book Dissolution takes

place against the backdrop of the dissolution of the monasteries and sees

Matthew Shardlake, lawyer, hunch-back and supporter of Reform, sent by

Thomas Cromwell to a Sussex monastery to investigate a grisly murder and the

theft of relics. There is solid history, gripping plotting and detail, and

atmosphere you can taste, but not a lot of London.

himself in 21st-century London' which is just not so. He

finds himself in London in a short, but powerful, coda in the last few

pages - not at all what I'd call 'soon'. But as a book about Dadd and

attitudes towards mental illness in Victorian times this effortlessly

conjures its times and grips and impresses mightily.

himself in 21st-century London' which is just not so. He

finds himself in London in a short, but powerful, coda in the last few

pages - not at all what I'd call 'soon'. But as a book about Dadd and

attitudes towards mental illness in Victorian times this effortlessly

conjures its times and grips and impresses mightily.

o affair. The book paints an authentic-seeming picture

of London in the mid-60's, a time when the minor railways could still be

said to 'criss-cross London with a secret logic of their own'. The locations

and odd facts keep the London-interest factor high. (Evidently if you wanted

pornography in London in the 18th or 19th century

you went to Holywell Street which was amongst a warren of streets - demolished

in 1901 - at the bottom of Kingsway, where you'll now find the Aldwych

and Bush House. A character in

o affair. The book paints an authentic-seeming picture

of London in the mid-60's, a time when the minor railways could still be

said to 'criss-cross London with a secret logic of their own'. The locations

and odd facts keep the London-interest factor high. (Evidently if you wanted

pornography in London in the 18th or 19th century

you went to Holywell Street which was amongst a warren of streets - demolished

in 1901 - at the bottom of Kingsway, where you'll now find the Aldwych

and Bush House. A character in

knowingly grin at some of the

ways in which the fabric of London

has evolved and corroded, too. Involving and brutal fun.

knowingly grin at some of the

ways in which the fabric of London

has evolved and corroded, too. Involving and brutal fun.

Well here's a thing, and a lovely thing too. It tries to be an artefact and

a work of art in itself, and I'd say it succeeds. The presentation is wacky,

sparse and illustration-dominated and the order of the

information is alphabetical but eccentric. The Dust chapter contains pages

devoted to sewage, rubbish, cemeteries and pea-soupers, for example. So this is not a book for looking

stuff up in. The facts

mostly match the presentation for originality, but it's arguable that they

play second fiddle. Another way of putting it is that if you don't like the

style you might find getting at the content a bit frustrating. But if you love the look

you'll love the book.

Well here's a thing, and a lovely thing too. It tries to be an artefact and

a work of art in itself, and I'd say it succeeds. The presentation is wacky,

sparse and illustration-dominated and the order of the

information is alphabetical but eccentric. The Dust chapter contains pages

devoted to sewage, rubbish, cemeteries and pea-soupers, for example. So this is not a book for looking

stuff up in. The facts

mostly match the presentation for originality, but it's arguable that they

play second fiddle. Another way of putting it is that if you don't like the

style you might find getting at the content a bit frustrating. But if you love the look

you'll love the book.

And

here's another book which to hold is to want, but you're not sure why.

It's a facsimile reprint of one of Phyllis Pearsall's first A-Z London

street atlases, printed in 1939, and so showing London before the Blitz

and and all the subsequent post-war redevelopments. And it's a facsimile

even down to the yellowing pages, with authentic spots and stains. But

what use is it? Well, as a Londoner you can look up where you were born,

where you live, where you used to live, that sort of stuff. It has those

little one-page maps of shops and cinemas, many long gone, where you might

remember buying your school uniform, say, or seeing your first French

film, the one where

Isabelle Huppert took off her...well you know the sort of thing. There's a

sweet fold-out Pictorial Map of London, with little 3D buildings on it,

stuck in the back. I liked the comprehensive annotated list of places of

interest too, from which I learned that the London Museum used to be in

Lancaster House by Green Park. This section also contains a list of

London's City churches, with asterisks by the ones which survived the

Great Fire; but this list itself would soon need revising as the Blitz was

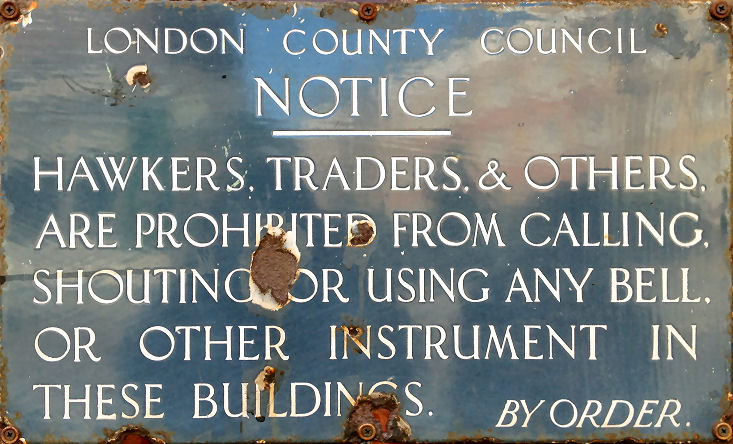

just a few years away. A more arcane pleasure is the list of the streets

renamed with the coming of the LCC (London County Council) which was done

to rationalise confusingly similar street names which were confusingly near to

each other, or not. A book of incidental pleasures, then, but a sweet and

loveable little

thing, in its handsome slip case.

And

here's another book which to hold is to want, but you're not sure why.

It's a facsimile reprint of one of Phyllis Pearsall's first A-Z London

street atlases, printed in 1939, and so showing London before the Blitz

and and all the subsequent post-war redevelopments. And it's a facsimile

even down to the yellowing pages, with authentic spots and stains. But

what use is it? Well, as a Londoner you can look up where you were born,

where you live, where you used to live, that sort of stuff. It has those

little one-page maps of shops and cinemas, many long gone, where you might

remember buying your school uniform, say, or seeing your first French

film, the one where

Isabelle Huppert took off her...well you know the sort of thing. There's a

sweet fold-out Pictorial Map of London, with little 3D buildings on it,

stuck in the back. I liked the comprehensive annotated list of places of

interest too, from which I learned that the London Museum used to be in

Lancaster House by Green Park. This section also contains a list of

London's City churches, with asterisks by the ones which survived the

Great Fire; but this list itself would soon need revising as the Blitz was

just a few years away. A more arcane pleasure is the list of the streets

renamed with the coming of the LCC (London County Council) which was done

to rationalise confusingly similar street names which were confusingly near to

each other, or not. A book of incidental pleasures, then, but a sweet and

loveable little

thing, in its handsome slip case.